Love them or hate them, the Nobel Prizes in Science remain some of the highest accolades in the world. Awarded almost annually by the Nobel Foundation and Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, the prizes honor individuals who’ve made outstanding contributions to physics, chemistry, and medicine. Some say the Nobel prizes fail modern-day science. Others have called them an absurd way of honoring achievement.

For their part, the Nobel Foundation probably thinks their awards help grease the wheels of progress and keep researchers doing the things they’re doing. One thing is for sure — the prize winners’ achievements are nothing short of extraordinary.

Here’s a brief breakdown of the 2018 Nobel Prizes in Science award winners, along with an explanation about why their work matters. (In case you missed it, here’s our breakdown of last year’s winners.)

Physics

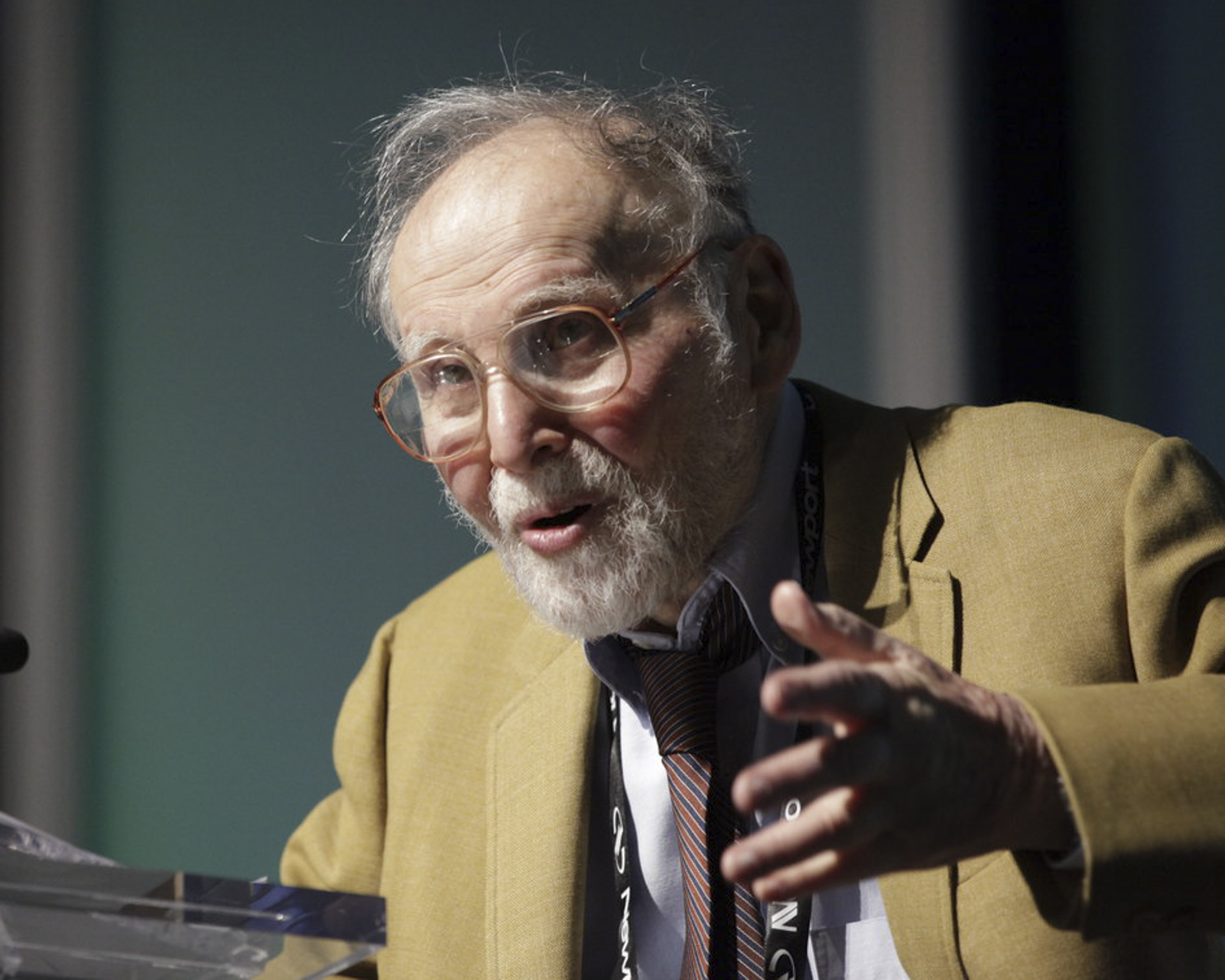

Winners: Arthur Ashkin, Gérard Mourou, and Donna Strickland

Why they won: Arthur Ashkin from Bell Laboratories in Holmdel, United States, was awarded the prize “for his groundbreaking inventions in the field of laser physics.”

The second half of the award was granted to Donna Strickland and Gérard Mourou for their chirped pulse amplifications, “a method of generating high-intensity, ultra-short optical pulses.” Strickland is a researcher at the University of Waterloo in Canada. Mourner is from École Polytechnique, Palaiseau, France and University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Why it matters: Ashkin’s lasers can be used like “optical tweezers” to manipulate particles as small as atoms, to probe how they function in biological systems. This sounds pretty sci-fi but it’s been widely used in the real world since Ashkin made his breakthrough in 1987. The minuscule tool may be used to unlock the ever-allusive secrets of the quantum world, and aid in the emerging field of quantum biology.

Through their research, Strickland and Mourou cleared the way for scientists to generate the shortest and most intense laser pulses ever created by humans. By stretching the laser pulses out over time, then amplifying the pulse, and finally compressing the pulse, they were able to pack a ton energy into a small amount of space. Chirped pulse amplifications are now used in millions of corrective eye surgeries each year. The two researchers made their first breakthrough in 1985.

It’s also important to note that Strickland’s win makes her only the third woman to win a Nobel in physics and the first woman in 55 years to be recognized with the prize.

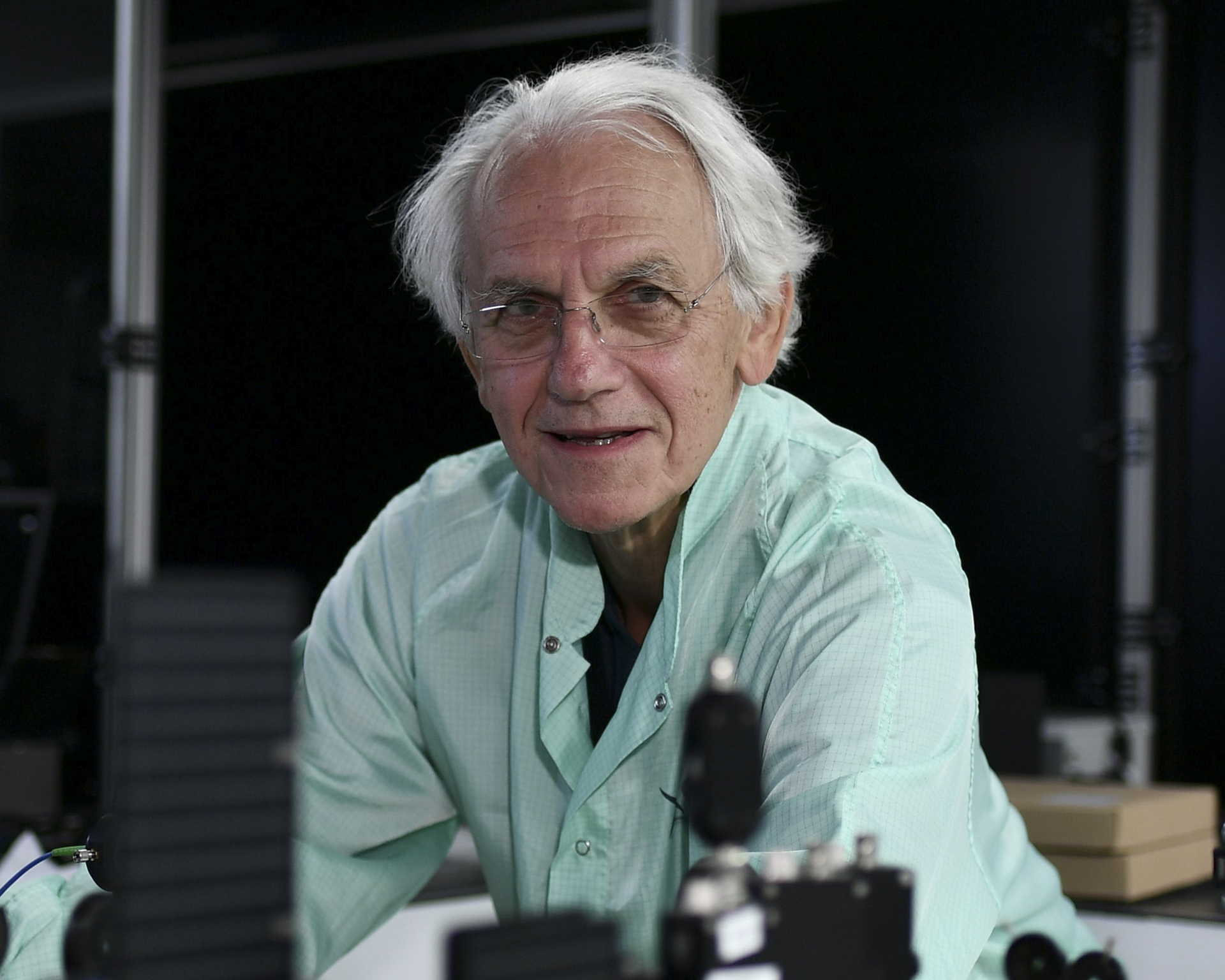

Chemistry

Winners: Frances H. Arnold, George P. Smith, and Gregory P. Winter

Why they won: Arnold, from the California Institute of Technology, was awarded the prize “for the directed evolution of enzymes.”

Smith and Winter won “for the phase display of peptides and antibodies.” Smith is from the University of Missouri, Columbia and Winter is from MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Why it matters: The winners each used genetic change and selection—inherent aspects of evolution—to create proteins that chip away at some of the chemical conundrums faced by humanity.

In 1993, Arnold conducted the first directed evolution of enzymes, a class of proteins that kickstart chemical reactions. Over the next 15 years, she refined her technique, enabling the production of new enzymes that allow for chemical manufacturing techniques that are less harmful to the environment. Today, these enzymes are used to fabricate everything from pharmaceutical drugs that save lives to biofuels that could help save the planet as alternatives to fossil fuels.

Smith made his breakthrough in 1985 with the development of phage display, a method in which a bacteriophage (a virus that infects bacteria) is used to create new proteins. Winter later used this method for the directed evolution of antibodies that led to new pharmaceuticals, the first of which was Adalimumab, used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and inflammatory bowel diseases. More recent pharmaceuticals created through phage displays have been used to neutralize toxins and cure metastatic cancer.

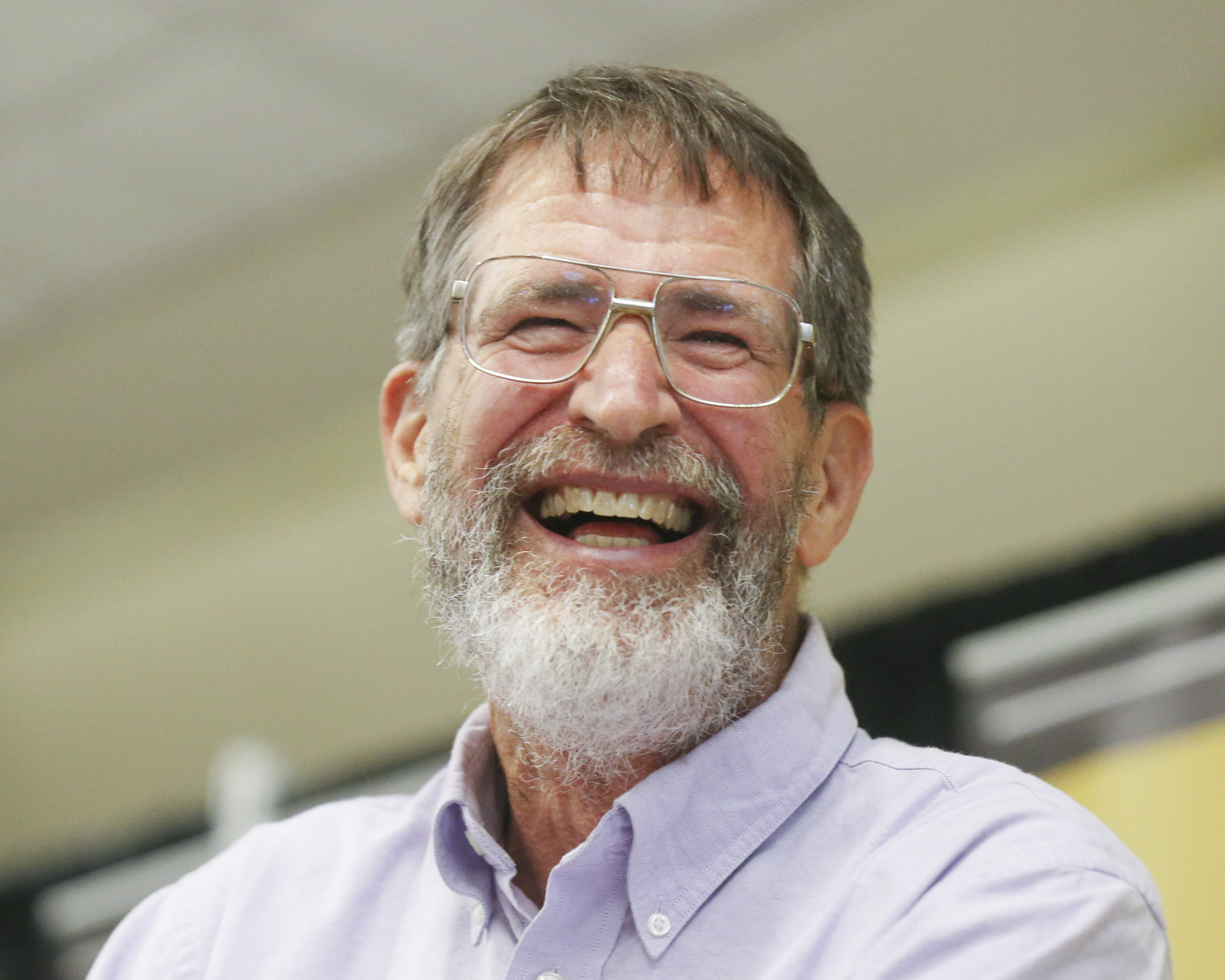

Medicine

Winners: James P. Allison and Tasuku Honjo

Why they won: Allison and Honjo share the prize “for their discovery of cancer therapy by inhibition of negative immune regulation.”

Why it matters: In his research, Allison investigated a protein found on immune cells, which were known to act as a braking mechanisms for the immune system. The researcher’s breakthrough came when he recognized that, by easing off the brake, immune responses could be accelerated to target tumors. Allison’s innovative approach has since been turned into therapies, including for the treatment of an advanced form of skin cancer.

Honjo, meanwhile, identified another immune-cell protein, which also acts as a brake, but functions differently than the one studied by Allison. Over the following years, Honjo unraveled the role of the protein, while he and other researchers leveraged the findings to develop new and effective treatments for cancer patients.