“Committing to mixing an album yourself makes you suddenly not accept a single frequency that’s not meant to be there when you were actually recording.”

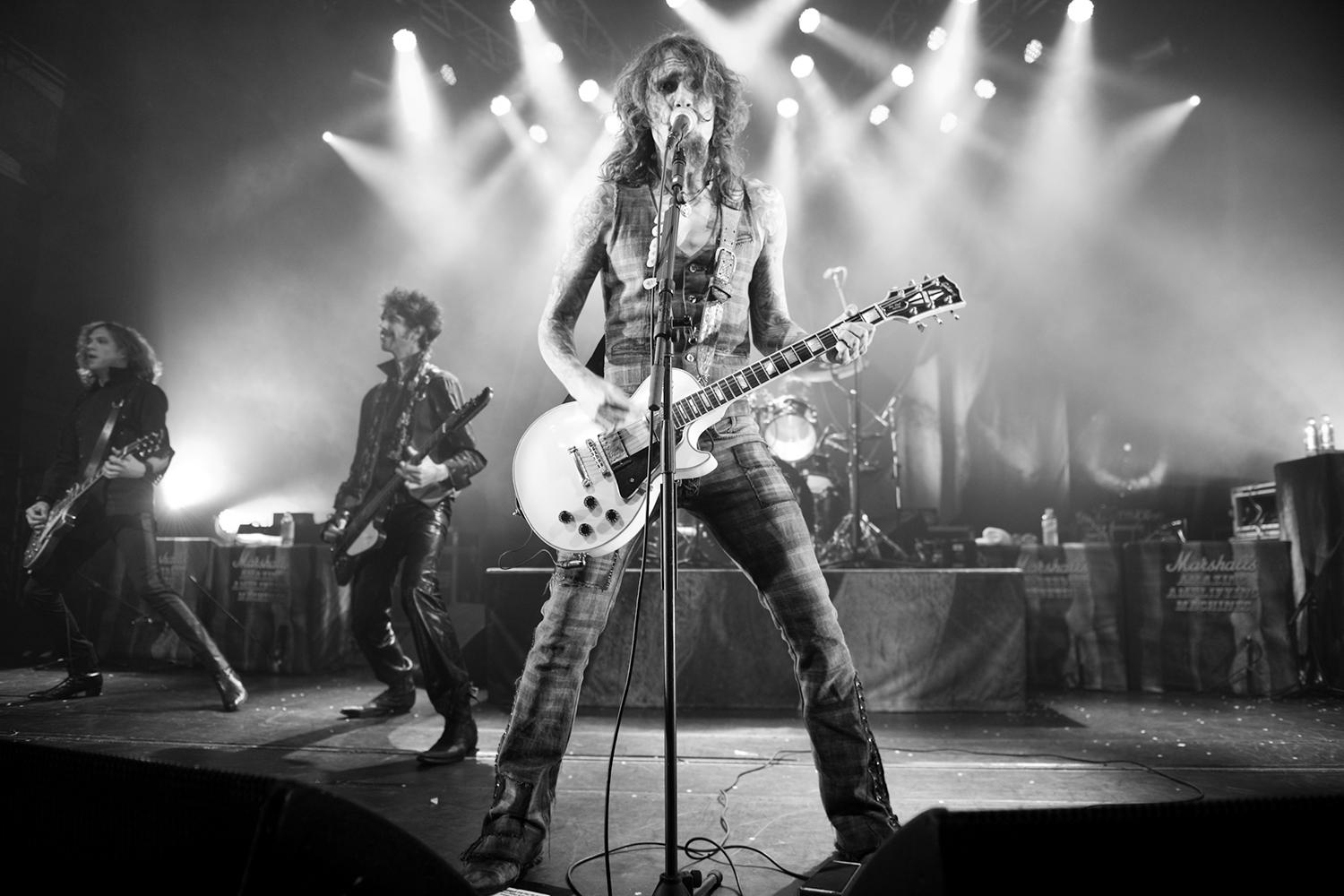

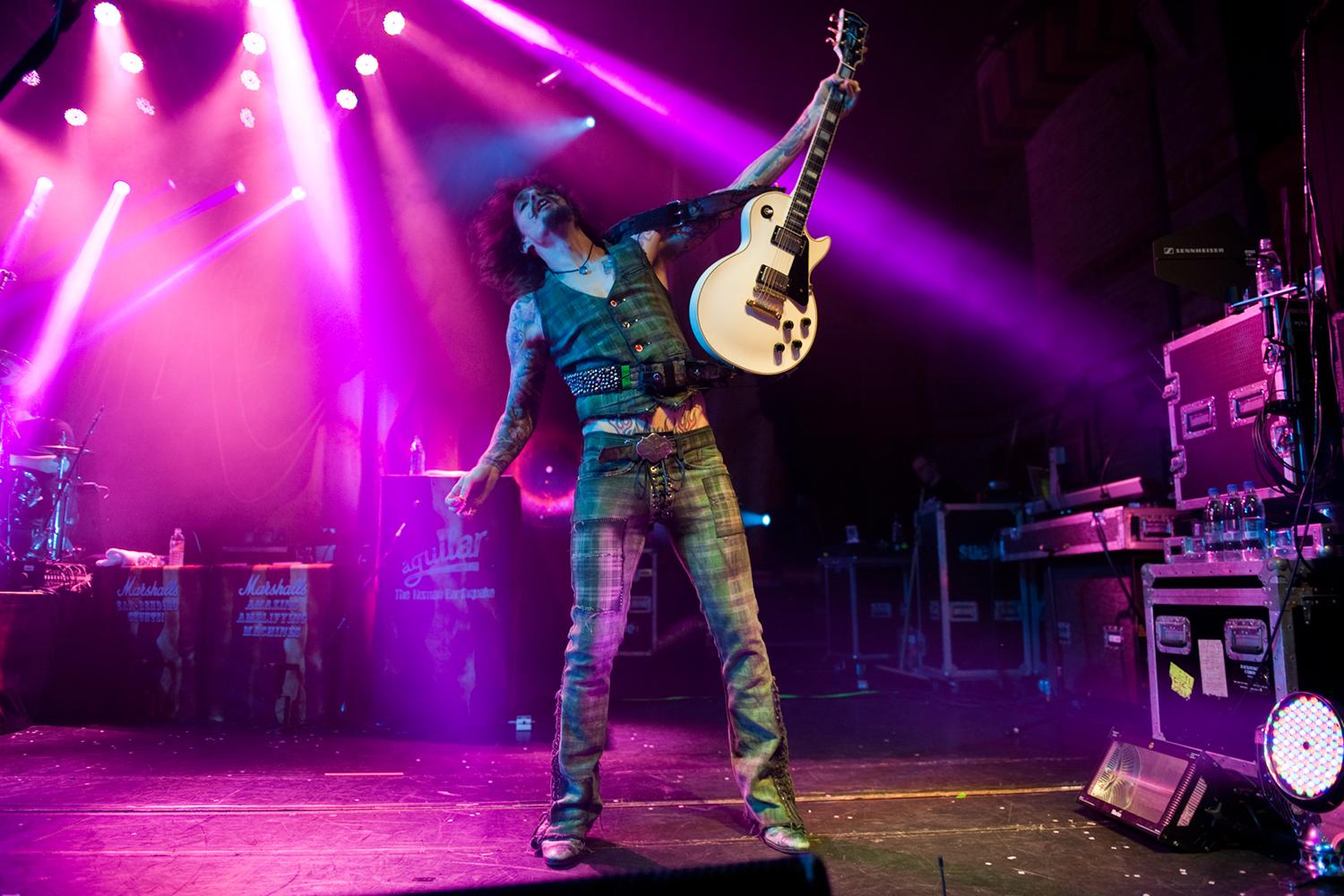

Dan Hawkins of The Darkness strives to be a cut above the norm in everything he does. When Digital Trends called to discuss the postmodern glam band’s incendiary new album, Last of Our Kind (out today on Kobalt on various formats), Hawkins was just finishing up some yardwork. “I’m trying my hand at topiary,” he explains with a chuckle. And how did that go? “Fucking really badly. Once you’ve cut something too far, that’s it. And you can’t go back, can you?”

Some may think The Darkness took the glam thing too far on its 2003 debut Permission to Land, which featured the massive singalong hit I Believe in a Thing Called Love, but the British foursome has always been shrewd enough to know just exactly where that fabled clever fine line lies. Last of Our Kind, their first album in three years, exhibits mastery of the form, from the pure rawk drive of Open Fire to the guitar-god frenzy of the title track to the incendiary thrust of Hammer & Tongs.

The key of Kind’s overall aural success lies in producer and guitarist Hawkins taking a firmer hand all throughout the recording process. “Mixing the record was interesting,” he reports. “One of the challenges, structurewise, was making sure I left enough to get the solos loud as we like them. It’s funny — you can have a vocal sitting in the same frequency range, and it’s not troubling you at all. But you start getting the guitar in there at the same volume, and you’re clipping in all sorts of ways. It’s a real struggle to get it right sometimes.”

After putting down his hedgetrimmers — here’s hoping there wasn’t a bustle in your hedgerow — Hawkins told DT all about his high-res audio leanings, when and when not to EQ, and the merits of recording digitally despite his love of tape.

Digital Trends: You know what I’m going to ask first — did you go 96/24 when recording this album?

Dan Hawkins: Yeah, I went 96 on this one. I can’t explain my reluctance to go higher this time, but maybe the next album I’ll do 192. Some people swear by it, and some people swear there’s no difference.

Have you felt a difference from what you did for the first couple of albums, which were probably at 44.1/16?

That’s exactly right. My ears have changed over the years anyway, so I’ve gotten better at detail. Maybe, at the time, on the first album [2003’s Permission to Land], I wouldn’t have been able to tell the difference. Now I can, yeah. There’s a little more depth to the sound.

I’m a high-res guy, and I only want to listen to 96/24 or higher. I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again: I can’t even listen to MP3s anymore.

Oh, tell me about it. It just gets annoying after a while, doesn’t it? It’s even made me reach back to vinyl. MP3s are noisy, loud, and distorted.

Some people claim they can instantly tell the difference between 192 and 96.

When you’re actually putting stuff down while you’re producing, you don’t have time to analyze one rate from another and flip between the two, because you’ve got one session going, then you’re jumping to another. When you commit to a sound you think is good, every producer or engineer has that thing where the light goes to green, then that sound is good to go. You’re not going back and thinking whether that sound was good enough or whether it was completely perfect.

“Some people swear by it, and some people swear there’s no difference.”

Being better at hearing all the details probably helps you when you’re in the production chair. You can tell if something’s missing from your guitar tone, what your brother Justin is singing, or what the other guys in the band are playing. You know if it’s not quite there yet.

Yeah, it does help. What I learned in the approach for this record is that I knew I was mixing it at the end myself, rather than going to anyone else. That had a big effect on the way I recorded things. Normally, when we’ve worked with other producers, by the time we get to the mixing, I’m ready to hand it over to someone. (laughs) You’re normally just burned out by then.

But then you don’t get what you heard in the studio. When people hand it off on the back end and then listen back, they say, “This is not what I signed off on in the studio.” That’s got to be frustrating.

Exactly. I read something that Steve Albini said. He said, “You cannot call yourself a producer unless you can mix the music that you produced to a level that you really like.” And I thought, “You know what? I still haven’t done that.” I keep making these records and imagining how they should sound, and they never come back the way I think they should.

The closest I got was the album I did with Stone Gods — Silver Spoons & Broken Bones (2008), which Nick Brine mixed, and I thought it sounded fantastic. But still, when I first heard it, I went, “Oh, you went that route.” (laughs) As it turns out, I did like it, but the fact was, it wasn’t how I heard it in my head.

Committing to mixing it yourself makes you suddenly not accept a single frequency that’s not meant to be there when you were actually recording. And I think that maybe bettered my engineering by about 100 percent.

So this time you knew before you were recording that you would be mixing on the back end?

Yeah, that was it. And in a way, that helped too, because I planned the whole sessions so I wouldn’t be burned out at the end. It was the most important thing. I was constantly thinking about the mix with literally everything that went down.

Is there one sequence in a particular song that you made an adjustment on because you knew you were the one mixing it later?

Let me think. On a song called Wheels of the Machine, it sounded like we hadn’t recorded enough on it and the guys were saying, “Are we finished with this? Is that all we’re going to do with it? Is it like the demo, where it’s going to be that raw?” And I knew that, in the end, the drum sound would fill most of the space, and it would sound huge. But on the way in, I wanted it to sound really organic, and get right the detail of what they were all playing.

Where did you decide to record the album?

We recorded it in Norfolk in my own studio called The Hawk’s Nest, which is kind of like a scaled-down version of the studio I used to own called Leeders Farm [in Wymondham, Norfolk]. I used to run a commercial residential recording studio, but I shut it down about a year or so ago and sort of downscaled. I turned it into a modular flight-case studio, because I wasn’t sure where I was going to live, you see. I finally got my studio on wheels! But I’m building a new studio as we speak, actually.

“It’s like holding someone’s oxygen and life support in your hands.”

What’s your main board?

I mainly work on lots of different individual mic preamps that I’ve collected over the years. Everything comes in like that, and I monitor off of a Chandler EMI TG — the little mixer, the Mini Mixer. But I got mine extended to 32 channels rather than the standard 16. It’s really nice. It’s kind of like a vintage API desk, I suppose. It’s got a really great sound.

If you had the chance to record to tape, would you do it?

Oh, 100 percent. I like recording digitally, but I try to not do much editing. I like to capture as much of a whole take as I can. I come from a tape background — I might have been one of the last to learn on tape, really. As I was learning, there was tape everywhere — ADR in certain studios, and then pretty soon it went straight to digital. So I kind of learned both at the same time.

That’s a good thing, because you understand how to capture a vintage sound in a modern way, which many people are not able to do.

Yeah, but I think you can go too far, can’t you? It’s hard not to, isn’t it? There are so many choices, and you can EQ the shit out of stuff. You can EQ things with certain plug-ins too.

To some degree, you could EQ the feel right out of a track, and then it sounds too clinical. And being too clinical with Darkness music would leave the listener too cold.

It’s the dynamic as well. If you’re dialing in shit-tons of EQ, you’re losing a lot of the dynamics. I’d rather have two snare mics than reach it by EQ, if I can help it. There was minimal EQ on any of the drums coming in. It was much more about getting the mikes in the right place.

With the guitars, I was lucky enough to have a chance to buy some of the original Trident Audio [S20] mic preamps, from the original Trident Studios [in London]. These things have tracked David Bowie and T. Rex records. Funny enough, when I was working with Roy Thomas Baker, he said, “If you’ve ever got the chance to get some Trident mic pre’s, get them, because they’re the best things for guitar.” They’re his favorite mic pre’s of all time, specifically for guitars. They came up on eBay, so I jumped on them — and I’m glad I did. I did a shootout with them and all the other mic pre’s I’ve got, and there’s just something about them. The best way to put it is they just stick the guitar right on the speaker.

As an example, I’m thinking of that clean, classic solo you take on the title track. Was that a Trident moment?

Yes, yeah, 100 percent. That would have been a mix of a Beyerdynamic M160 mike and a Shure SM57 probably off-axis with that room. That’s an extraordinary solo, isn’t it? You don’t really hear solos like that anymore, do you? It’s got its own character.

And since Justin goes for those super-high vocal runs, you have to figure out how to balance that solo in the mix of the bed track.

Absolutely. There’s a huge amount of fader rides on that song, particularly going into that section. I did a combination in real time of writing the automation of the fader. Sometimes I write it with a mouse, and sometimes I’m just trying not to clip the bloody thing! (chuckles) Sometimes it’s easier to pinpoint where I am and see what I can get away with, looking at it from that point of view.

“With tape, you always had your own life in your hands — and quite literally, with some artists.”

Getting that guitar solo’s sound was a challenge, that’s for sure. I used to just compress the shit out of guitars, on the back end. I tend to do that on the way in now, with guitar pedals. You’re recording what you want to get in the end, so you use compressors more with the solos.

Anytime you mention tape, I think of your mentor Roy Thomas Baker and him working with Queen on Bohemian Rhapsody, where if they weren’t careful, they could have totally worn through the oxide of that same critical piece of tape.

Oh my God. Roy Thomas Baker produced our second album [2005’s One Way Ticket to Hell… and Back]. It was around when Ampex had just shut down, and they stopped producing tape. I couldn’t even tell you how much we paid for it. To make a record with Roy, he needs 36 reels of tape! (laughs) it’s like holding someone’s oxygen and life support in your hands.

The reason why digital is so great is I’ve got backups of backups. I’ve got complete faith in what I do, and the tech support I have is really good. You can’t really have any major disasters. But with tape, you always had your own life in your hands — and quite literally, with some artists.

Speaking of Roy, do you have a favorite-sounding record he worked on, one you consider your personal benchmark for sound quality?

I really like Queen’s Jazz (1978), the one they did in Switzerland [at Mountain Studios in Montreux]. That’s one of the albums that got me into recording. Specifically, it was the drum solo on Fat Bottomed Girls, where the drums go from one speaker to the other. It might have been that point as a young boy when I went, “My God, these speakers!” You don’t even realize things can happen like that in stereo when you’re six or seven years old. (laughs)

And I think Roy is the master. When he works his fader, he doesn’t mess around. If something is meant to be heard, it’s incredibly loud in the mix. It’s just a really fat-sounding record to me.

That production style is in your DNA, because we don’t really hear many records like Last of Our Kind anymore. You capture the bigger vibe without losing that sense of character and dynamic range.

Indeed. That’s what I strive for. But I’m definitely guilty of getting caught in the traps. And you have to go there to come back sometimes, don’t you? It’s better to get it right in the first place than trying to fix it in the mix. You have to have a clear idea of what it is you’re going for.

I like to get the band in the zone, and have a listen back after the first take and see if I think people are nailing it. And not criticize, but to encourage and say how good this is — but that might have taken the band a half hour getting there.

I have this thing where I like people to listen when the adrenaline is gone, you know? They calm down and go off and do something, and then we have it not be a big deal. Being a recording musician and understanding completely about red light fever, you just need to look at it with not that overly critical mindset — you almost need to listen more to what other people are doing on your take than what you are. You might end up changing little bits no one will ever care about.

Sometimes when you’re pushing or pulling rhythmically against the track, that’s what makes it so good. That’s quite literally the essence of groove. When someone’s ahead and someone’s way back — normally bass player and guitarist, respectively — there’s no such thing as perfection, right there.

Is there one song that’s your favorite mix on the record, the one where you feel you got everything nailed?

Ooh, God, that’s a tricky one, really. I am pretty happy with the album. Sometimes you’re just so over it after it’s done, sometimes for years — but not on this one. We’re all listening to it again.

I think it’s pretty cool. Open Fire came out pretty good in the mix. Last of Our Kind, the title track, is exceptionally good, because there’s so much going on in that song. A lot of that track is in mono until the chorus, and that kind of gives it a big push. There’s all manner of mandolins and wailing harmony guitars chugging along, band vocals, and percussion. There’s quite a lot going on there.

And that’s another good reason why 96/24 is the only right way to hear it. There’s too much going on here to miss out.

Exactly. It is important. Otherwise, why even bother, you know?